Stanford Magazine

August 23, 2017

By John Roemer

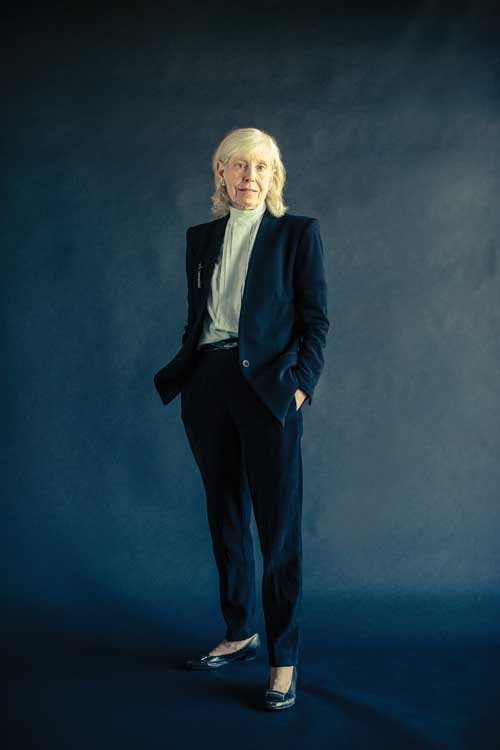

For four decades, her leadership has helped define the ethics of power and parity.

By John Roemer

Photography by Timothy Archibald

Before she was the nation’s most frequently cited scholar on legal ethics, or the author of more than 20 books, or an influential voice in the ear of circuit court judges, Deborah Rhode handled run-of-the-mill divorce cases. She was doing just that, as a law student at a civil legal aid clinic in New Haven, Conn., when she set her life’s course.

Her clients there sought help with divorces they could not afford because local lawyers had priced them out of the market. “If you were low-income, you were out of luck,” Rhode says. “Lawyers were then charging $1,000 to fill out the paperwork.” Incensed, she and her colleagues sought a way around the problem. “We put out a kit for uncontested divorces,” she says. The bar association threatened to sue the clinic for the unauthorized practice of law. But an underresourced women’s support group in town offered to put its name on the kit to foil the protectionists. “They told the bar to go ahead and sue them for their coffee pot.” The lawyers backed down.

That’s when Rhode realized she wasn’t cut out for lawyering at the retail level. Individual cases were too stressful. “I was angry all the time,” she says of her reaction to the injustices she dealt with at the clinic. “I didn’t have the stomach for direct services.” But advocacy through academia would suit. She decided to write about the unauthorized practice of law for the Yale Law Journal.

Her co-author was her classmate and future husband, Ralph Cavanagh. The pair surveyed outcomes in civil court of uncontested divorces in which parties used the kit versus those in which couples had legal counsel. “The lawyers made the same number of mistakes” as the couples themselves, Rhode says. The article’s conclusion melds the practical with the ethical: “The bar should not be making the rules regulating its own competition.”

Rhode joined the Stanford Law School faculty in 1979 as its third female professor, and she has spent the past 38 years articulating hard truths about women, power, leadership and the search for justice. Speaking honestly — and with passionate eloquence — has been the through-line of her long career as the conscience of the legal profession. Her forthcoming book on cheating rejects the “everybody does it” rationale but comes with a clear-eyed acknowledgment that ubiquity in deceit is uncomfortably close to a universal human truth. Cheating: Ethics and Law in Everyday Life is due this fall from Oxford University Press.

Rhode was one of the first law professors to offer a course on leadership. “I backed into the field following my interest — and now three books — on women and leadership,” she says. Her interest and scholarship got her invited to a national conference on leadership at Harvard, where she found she was the lone legal academic among some 200 participants. “It seemed to me then and now that something was wrong with that picture.” Law is the trade of many who end up in charge — 26 of 45 U.S. presidents have been lawyers — yet law schools have tended to ignore the subject. That began to change after Rhode created Lawyers and Leadership, a popular course at Stanford that distills her thinking about who ascends to power in politics and business, and why. Several other law schools now offer courses on the subject. The ideas in Rhode’s 2013 book, Lawyers as Leaders, her pedagogy and her outspoken social critique of the quality of leadership in the United States have been brewing for years.

Speaking honestly — and with passionate eloquence — has been the through-line of her long career as the conscience of the legal profession.

“It’s a shameful irony that the occupation that produces the nation’s greatest share of leaders does so little to prepare them for that role,” she writes in a June Stanford Law Review article. “Yet the need for effective leadership has never been greater.”

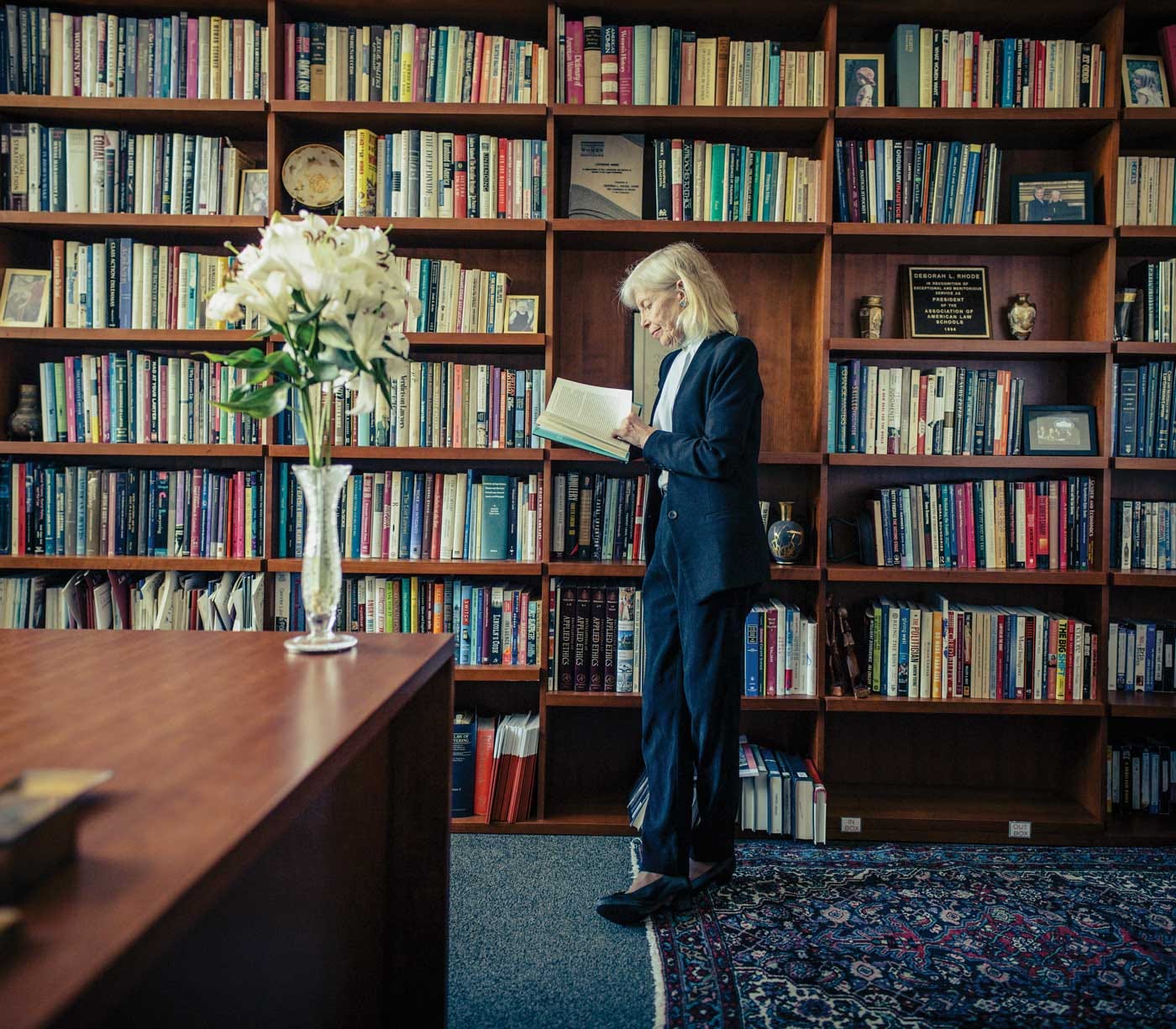

Sitting in her tidy office one Tuesday afternoon on the third floor of the William H. Neukom Building, Rhode sips from a stemmed glass of Diet Coke over ice. An elegant vase of fresh lilies ornaments her desk. On the wall nearby is a framed four-panel drawing of British barristers arguing. “Look, this isn’t getting us anywhere,” says one. “Well, let’s just be honest with each other,” is the reply. The third panel shows them gazing at one another silently. In the fourth, one finally speaks. “You first,” he says.

That afternoon, as Rhode chats with a reporter, the phone rings. “Hello, Merrick,” she says, taking a return call from President Obama’s Supreme Court nominee Merrick Garland, whom President Trump supplanted with Neil Gorsuch. Rhode is promoting a star pupil to be a Garland clerk at the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, where Garland is chief judge. But first she devotes a moment to commiseration for Garland’s failure to attain the high court bench. “You were just the first casualty,” Rhode tells him. “At least you got a lot of coverage on late-night television.”

Rhode and Garland were Supreme Court clerks together, she for Thurgood Marshall, he for William J. Brennan Jr. They have remained close. “I sent him a picture of a bench I saw here at Stanford with a sign, ‘Reserved for Merrick Garland,’ ” she says after concluding the call.

Now it’s time for class. In her leadership course, Rhode combines rigorous scholarly inquiry with a glittering array of guest speakers. Today’s 40-page study guide on moral leadership has a section outlining the historical framework supplied by Machiavelli and a section on “How the Good Go Bad,” featuring rogue traders in the financial markets and leadership failures in the auto industry. Speakers over the semester have included Stanford President Marc Tessier-Lavigne; professor of political science Michael McFaul, ’86, MA ’86, a former U.S. ambassador to Russia; former Army lawyer and three-star general Dana Chipman, JD ’86; and former secretary of state Condoleezza Rice, a Stanford political scientist. Earlier iterations of the course featured four-time cabinet member George Shultz, now a distinguished fellow at the Hoover Institution, and former NAACP president Ben Jealous.

This Tuesday, it’s Rhode in a solo turn. Today’s lesson is on moral leadership. It opens with readings from Machiavelli, including, of course, a teaching from The Prince, chapter XVII, “Of Cruelty and Clemency, and Whether It is Better to Be Loved or Feared.”In her mind, and in the minds of the students she will speak with shortly, the moral life of the 16th century collides with current events. “Trump gave feminism a jolt,” Rhode says. “Of course he’s a real wake-up call. Many women thought the woman problem, if not solved, was well on the way.”

‘It’s a shameful irony that the occupation that produces the nation’s greatest share of leaders does so little to prepare them for that role. Yet the need for effective leadership has never been greater.’

The Prince, she tells her students, is the most classic account of moral leadership. She notes that the book came at a time of enormous political turbulence. The government in Florence underwent bloody coups and foreign invasions. Machiavelli was imprisoned and tortured. Popes banned his book. “He claimed famously that it’s better to be feared than loved,” she says, advancing the topic to modern times by paraphrasing a comment from New York Times op-ed columnist David Brooks: “If political leaders don’t have a moral compass, they aren’t going to get one at the White House.”

There’s a discussion of the dirty-hands dilemma, named for the Jean-Paul Sartre play Les Mains Sales, in which a moral quandary results from having to choose between repellent options. Rhode cites a corporate executive who spoke at Stanford’s Center on Ethics, which she founded and directed for a time. The executive told of being torn between having to bribe customs officials in an impoverished country, in violation of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, and fulfilling his goal of buying and importing goods made by poverty-stricken women seeking to feed their children. “This guy had a PhD in philosophy from Stanford, and he wasn’t sure how to deal with it,” Rhode says.

Now we wonder to what extent Americans are resigned to dirty hands among their leaders, Rhode notes. Political theorist Michael Walzer, whom she cites, agrees with Sartre’s character Hoederer, a communist leader, when he exclaims, “I have dirty hands right up to the elbows. I’ve plunged them in filth and blood. Do you think you can govern innocently?” Rhode updates that with a reference to the TV series The West Wing, in which the president and his chief of staff debate assassinating a foreign minister involved in terrorism. That would be wrong, the president protests. The aide insists he must do it anyway. “Why?” the president asks. “Because you won,” the aide replies.

The lively classroom debate that follows, in the best Socratic tradition, finds no easy answers. What would you have done? Rhode asks her students. The session ends with a sequence of video clips compiled by a student, including one of Frank Underwood in House of Cards, who, encountering a neighbor’s dog hit by a car and whimpering in pain, calmly strangles the animal, wipes his hands clean and says, “Moments like this require someone who will act, who will do the unpleasant thing, the necessary thing.” Comments Rhode, “Literally, dirty hands.” Elsewhere, she notes, a website has a quiz asking who spoke those words, Frank Underwood or Machiavelli.

From her first days as a Yale undergraduate, Rhode was a keen student of the kind of sticky situations that would inform her search for clarity of thought. An early lesson exposed her to male privilege, led to her discovery of feminism and propelled her on her long march toward opposing oppression.

When Rhode arrived in New Haven in 1970 as part of Yale’s second-ever undergraduate class to include women, she found herself bucking a 200-year school tradition of masculine advantage and female exclusion. At an alumni reunion not long before her matriculation, she learned, two striptease artists had performed to an audience that included the university’s provost, an event that Rhode said captured the flavor of the times. “What is the official Yale position toward this?” someone asked the provost when the women had finished their acts. He gave the questioner a stern look, according to a contemporary observer, William F. Buckley Jr. “Yale’s position is that the Second One is better than the First,” the provost said.

Rhode recounts the incident in her 2014 book, What Women Want: An Agenda for the Women’s Movement. She points out that when she entered the academy, it was pretty much a closed male shop, where some maintained an actively hostile attitude toward women.

Yale administrators, when the school first admitted women, were evidently oblivious to any implied insult as they described the school’s new coed student body as “a thousand male leaders and 250 women,” Rhode reports dryly.

“It wasn’t sexism on steroids, exactly,” she says. “But it was a big undercurrent. Women were an unwanted minority. There wasn’t even a term for sexual harassment.”

The reunion affair wasn’t Rhode’s only stripper story. After Yale and her clerkship with Marshall, she headed west in 1979 to become a Stanford law professor, joining civil and criminal procedure scholar Barbara Babcock and assistant professor Carol Rose, who left Stanford at the end of that school year. The rest of the faculty was composed of 36 male professors.

Rhode found Stanford little different from Yale. Still, she says, she was unprepared for how lonely it would be. “I had done no research at that point on gender bias or gender stereo-types. One thing that struck me as odd was how often I was mistaken for Barbara Babcock. I mean, she was tall and brunette,” says Rhode, who has blond hair and is much shorter than Babcock. “At one point Barbara and I circulated a memo asking the faculty to perform a thought experiment: What if you were the only man teaching at the law school? It was like a feather falling into a well. It became known as the ‘Barbara and Deb need a friend’ memo. That somewhat missed the point, though it was true.” She said it reminded her of the many times at the Supreme Court when, despite their obvious dissimilarities, Sandra Day O’Connor and Ruth Bader Ginsburg were mistaken for each other by confused male lawyers. At one point, Rhode recalls, women advocates presented the female justices with T-shirts reading, “I’m Ruth, Not Sandra” and “I’m Sandra, Not Ruth.”

‘At one point Barbara and I circulated a memo asking the faculty to perform a thought experiment: What if you were the only man teaching at the law school? It was like a feather falling into a well.’

Her most vivid memory of her early days at Stanford Law: At then-dean Charles Meyers’s retirement dinner in 1981, alumni threw a party at the local country club and hired a stripper to perform. “None of us women present could quite believe it was happening — including the dean’s wife,” Rhode says. “In [Meyers’s] defense, it wasn’t he who made the arrangement, but there was a reason why his pals thought he’d be amused. The dean appreciated the thought behind the invitation and, well-fortified by bourbon, warmly embraced the invited guest.”

Rhode’s tales of boorish campus hijinks enliven a scholarly tome, display her sense of humor and disclose something about the breadth of her thinking. She’s a smart and witty scold. If Rhode has weaponized her intellect, she uses no cudgel but rather the rapier of moral suasion to skewer oppressive foes.

“Deborah Rhode has played an extraordinary role in the life of Stanford Law School,” former dean Kathleen M. Sullivan told Stanford in an email. Since transitioning back to practice (and becoming the first female name partner at a Top 100 law firm), Sullivan has continued to track Rhode’s work. “In her prolific scholarship on the legal profession and women and the law, she combines meticulous research with graceful and lively writing that gives her work a broad audience. She brings to her work the generosity and fair-mindedness that also characterize her interactions with her colleagues and students.”

Originally no feminist, Rhode had an epiphany during her undergraduate years, when she told a grad student adviser at Yale — Rhode describes her as a braless libber — that she wanted to study poverty. The woman gave her Simone de Beauvoir to read. That pioneer of social theory and political activism opened her eyes. “I can still remember sitting in the huge Yale library reading room and suddenly seeing the world in a different way,” she says. “De Beauvoir’s discussion of the subordination of women and its underlying causes made me see my parents’ marriage, my own relationships and the situation of female undergraduates at Yale in a new light.” She graduated summa cum laude in political science in 1974, then entered the law school.

In the 1980s, after Rhode had become a Yale trustee, she says she tried to get others on the mostly male board to recommend awarding de Beauvoir an honorary degree. “I encountered startling sexism,” she recalls. “ ‘How do we know she wrote the book?’ they said. ‘It might have been her husband.’ ”

At both Yale and Stanford, especially following the Dean Meyers retirement party, Rhode says she saw her path more clearly. Meyers had urged her to teach contracts to avoid being “typed as a woman,” as he put it. “I replied, with irony, that being typed as a woman would hardly come as a shock to anyone who knew me.” After the stripper episode, the decision came easily. “To hell with contracts,” she remembers thinking. “The law school needs a course on gender.” She began with a class on gender law and public policy. When she informed Thurgood Marshall that would be her subject, she says her former boss laughed. “Really? They need a course on [sex discrimination] at Stanford? It seems to come naturally to the rest of the country.”

Rhode’s prolific output, her choice of neglected yet crucial topics and her incisive thinking have brought her honors and influential posts. She has been on the American Bar Association’s Commission on Women in the Profession, and she founded the Stanford Center on the Legal Profession. The 30 books she has written or edited include The Trouble with Lawyers, an account of the vast problems facing the American bar; The Beauty Bias, which critiques the strangle-hold of appearance discrimination on our society; and Moral Leadership, a collection of essays she edited on the theory and practice of power.

Since the election, Rhode has criticized and prodded those in power. There’s been a law journal article on reproductive justice; a Washington Post op-ed titled “Six of the Worst Cuts in Trump’s Budget”; and a Daily Journal column deploring conservatives’ reproductive rights agenda that, she wrote, “would make a bad situation worse and place women’s reproductive autonomy at increased risk.”

In a book she’s drafting on character, she terms the lack of emphasis that today’s voters place on character “a worrisome trend.” During the 2016 presidential campaign, she writes, two-thirds of Americans did not think Donald Trump had “strong moral character,” and only a third thought he was trustworthy.

Rhode takes on eminent jurists too. When the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals’ then-chief judge, Alex Kozinski, ignored a nonbinding federal hiring plan that urged judges to hold off on recruiting third-year law candidates for clerkships until specified dates, Rhode was publicly outraged. Kozinski told the New York Times that he began to recruit promising clerks “at birth” and would have nothing to do with the rules. In 2008, Rhode made clear her view of Kozinski’s effort to interview Stanford Law students far earlier than the plan envisioned. “We had a meaningful exchange of views,” she said of her private dialogue with Kozinski. “He appears to have a sense of entitlement and to feel an insularity from accountability.”

Legal ethicist Stephen Gillers says Rhode deserves applause for her out-spoken public critiques. “I’ve watched her career,” he said by phone from his office at New York University. “She’s a force of nature. She’s energetic, determined, decisive and scholarly. She’s done more to emphasize the public respon-sibilities of the private bar than any other lawyer of her generation. I place her very high among feminist scholars and legal theorists.”

As Rhode takes stock of her career, she’s proud of her own leadership at Stanford Law and of the tangible outcome of her relentless efforts over the decades to advance women’s causes. In a quality-of-life survey she and others did when she chaired a Stanford provost’s committee on the status of women faculty, women law and engineering professors were shown to have the highest satisfaction levels of any cohorts at the university. “And yes, I worked endlessly to address gender-related issues as a member of the Law School faculty, both for students and colleagues, and now as co-chair of the Faculty Women’s Forum,” she says.

Access to justice, the issue that whetted her appetite for a career in scholarship and advocacy during her days at the civil legal aid clinic, remains atop Rhode’s agenda. Earlier this year — even though she was skeptical it would do any good — Rhode put together an open letter to Congress protesting a proposal to cut federal funding that assists nonprofit legal aid organizations. She gathered 1,000 signatures from legal scholars around the country supporting her view. “My colleagues need to focus more on access-to-justice issues,” she says, ever the advocate.

In many respects, Rhode is a realist, describing the problems with the world as she sees them. But Sullivan sees something else in her too. “Deborah has a wonderful and rare scholarly optimism — a belief that careful study and fair analysis can produce better outcomes for our profession and our society. She models all that is best about our profession.”

John Roemer has covered California lawyers and courts for 25 years.

https://medium.com/stanford-magazine/deborah-rhode-ethics-leadership-gender-law-5fd49dc43832